The Storm After The Storm: Coping with PTSD after Hurricane Katrina

by: Nia Burnett

It still haunts me.

The levee along the Inner Harbor Navigational Canal was among those that failed during Hurricane Katrina. Credit: Vincent Laforet/The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/24/us/decade-after-katrina-pointing-finger-more-firmly-at-army-corps.htm

There is currently a Wikipedia section about my life on the internet. If you google Effects of Hurricane Katrina on New Orleans, a Wikipedia page will surface. Under the Health Effects section, you will find the story of the survivors of Methodist Hospital. I can confirm the accuracy of our short little section since I was one of the survivors. I slept a hall over from the stack of dead bodies on the second floor.

I’m from New Orleans East, a suburban area containing the Audubon Louisiana Nature Center and Lake Pontchartrain (pronounced pon-cha-train), one of the largest inland seas in the world. My childhood was gumbo, walks along the lake, swim lessons, greenery and animals, and being wildly, deeply, and entirely obsessed and in love with the ocean (cue the Moana soundtrack). Ironically, it was my same beloved inland sea of Lake Pontchartrain that betrayed me when it flooded New Orleans East.

Aerial shot of the same levee breach as previous photo. Credit: AP Photo/David J. Phillip

I was 9 years old.

I was 9 years old when Hurricane Katrina, a behemoth of a storm, roared over southern Louisiana, bringing with her a violent, angry storm surge that devastated the still segregated Black neighborhoods of New Orleans. This is a story of environmental injustice and racism as much as it is a story of climate change, habitat loss, deforestation, sea-level rise, and overfishing. We cannot separate these topics. The destruction of Louisiana’s barrier islands, mangrove forests, and marshlands, its natural protectors, coupled with racist laws that left Black people vulnerable and on the front lines of tropical storms, created the perfect roux for a catastrophe.

My mother was a nurse at Methodist Hospital in New Orleans East, so her family could take shelter at the hospital. For me, it was exciting. We had our own hospital room, I felt a naïve sense of adventure, and my babysitter was giving us Snickers ice cream bars. She was probably feeding us to keep her mind off the feeling of uneasiness that settled in with the adults. But I was ready. I was ready to see who this Katrina was so that I could thank her for giving us a fun break from school. Boy, oh boy, oh boy, oh boy, was I never more wrong in my life.

The Hidden Strength of Katrina

Little did I know, our fate was written in the stars…if those stars were the racist-all- -white levee committee of the 1960s. We’re going to flashback 40 years to introduce you to Katrina’s predecessor who paved the way for her success, Hurricane Betsy. Betsy walked so that Katrina could run. In the 1960s, it was illegal for Black people to get home insurance in their own Black neighborhoods. New Orleans was, and still is, heavily segregated. The salty twang of chattel slavery reigned heavily in 1960s Louisiana. Black people reluctantly followed policies that kept them separate, but “equal”from the white community. The unequal distribution of resources and political power that existed in this state would create broken foundations for the Black community to have any proper disaster response in the future.

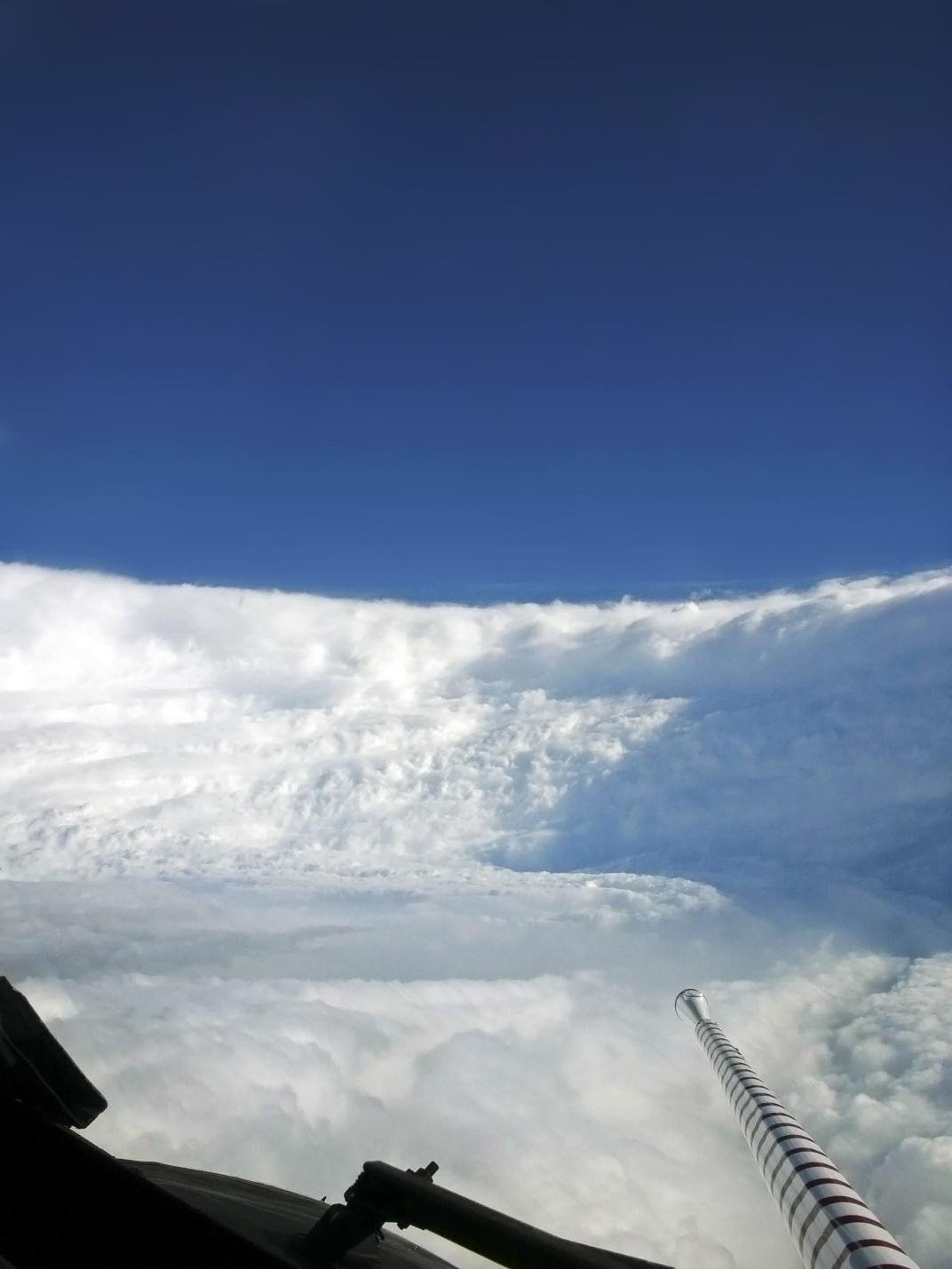

Eye wall of Hurricane Katrina in August 2005 before the storm hit the United States. Credit: NOAA WP 3D Hurricane Hunter, 2005. https://www.omao.noaa.gov/find/media/images/hurricane-katrina-eyewall

Environmentally, Louisiana had little foresight. There used to be many crucial marshlands and mangrove forests bordering coastal Louisiana which helped to soak up flood water from storm surges and tropical storms. With the development of the shrimping industry, however, mass deforestation ensued to make way for operations. While the state was able to benefit from this economic development, the depletion of natural barriers allowed for severe destruction and flooding from Hurricane Betsy.

To combat future storms, a levee council was formed to protect New Orleans. At the outset, this council was a great step, but there were clear missteps to address its inadequacies in design and execution that made it fall short. The levees were full of massive gaps where steel should have been due to engineering calculations and interpretation errors. To save $100 million dollars, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers decided not to implement the proper length of steel beams needed for the levees. The levee system surrounding the Greater New Orleans area was not structurally sound. They just looked the part. The following photos are the exact same Black neighborhoods in New Orleans. The black and white photos are Betsy, the color photos are Katrina, 40 years apart.

Flooded New Orleans in 1965 due to Hurricane Betsy. Credit: louisianastatemuseum.org

Greater New Orleans flooded 40 years later in 2005 due to levee failure from Hurricane Katrina. Credit: https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/hurricane-katrina-10th-anniversary-40-powerful-photos-new-orleans-after-storm-1516356

People sitting on their roof after Hurricane Betsy flooded New Orleans, 1965. Credit: https://www.nola.com/crime/2011/12/corps_of_engineers_says_its_no.html

People sitting on top of their home after Hurricane Katrina flooded New Orleans., 2005 Credit: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/eleven-years-after-katrina-what-lessons-can-we-learn-next-disaster-strikes-180960293/

Greater New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina hit. Credit: Times-Picayune Archive. https://www.nola.com/crime/2011/12/corps_of_engineers_says_its_no.html

An aerial shot of Greater New Orleans after Hurricane Betsy hit, 1965. It is identical to the 2005 flooding of Katrina. https://www.nola.com/hurricane/2015/09/50yearsago_hurricane_betsy_sla.html

Flooded Greater New Orleans, 2005. Credit: https://www.hearttoheart.org/katrina-10-years-later/

After almost 2 weeks of being trapped on top of a hospital building, traumatized and scared, we had no idea if we’d ever find a way out. I still remember the horrible rotting smell of those who did not make it just a hallway away. My whole family was aching and lost, desperate for help.

Then, we were rescued. The national guard airlifted my entire family away from flooded New Orleans toward California, our new ‘safe haven.’ I wanted to believe that the pain would be over, but that actually was just the beginning.

The Trauma After The Storm

Weeks after we landed in Los Angeles, I began showing symptoms of PTSD weeks after getting settled. It began with the creeping feeling that I was going to die immediately. This is where my insomnia was born. Then came the flashbacks. Then came the night terrors – horribly violent nightmares that felt more real than my actual reality. Every hurricane season, from that day forward, continued to be a season of heightened anxiety.

I left my childhood memories behind in Katrina. For the rest of my childhood, I always felt older than other kids. I carried the weight of trauma on my young shoulders before I could give voice to whatever I was experiencing. PTSD rocked my body, my mind, and my soul. I became withdrawn, angry, and silent. I hid away within myself, breaking down the microcosms of childhood nuance and innocence as I did.

I put up spiky, dense, emotional walls to protect myself from others and the world. I experienced what most adults would never go through before I hit double digits. How was I supposed to handle it when I didn’t know what was happening to me?

When I attended high school, an all-girl private high school that women like Megan Markle and Yara Shahidi graduated from, I met a teacher who helped me. For one of our journal assignments, we had to record our dreams and our feelings for the semester. My teacher informed me that she believed I was struggling with PTSD. That was the first time I had a name for what I was struggling with. At this time, let’s say 15, I was 5 years out of Katrina and dealing with repressed feelings of anxiety, depression, and PTSD that I had tried to keep at bay for years. Mental health has a nasty stigma in my culture, so my shame about myself only intensified.

Finding A Way Forward

My teacher gave me a way forward- she taught me how to record my dreams and to examine the relationship between my anxiety and the recurring nightmares I had from the disaster. She gave me a dream interpretation book that greatly helped me cope with the event. In my dreams, I always pictured myself trying to save large groups of people before a massive flood came. In my journal, I was able to express how I felt and was able to interpret the different symbols using the guide she provided me. That was the beginning of my long, long healing process. I eventually began seeking therapy when I hit college. While I haven’t found a therapist to stick with yet, I am still hopeful. For the first time, I felt like I was starting to find answers to an uncontrollable event that uprooted my life, and getting the closure I so desperately needed.

To help anyone out there who has faced something similar, I want to give you the advice that I never had access to as a survivor regarding your mental health after a disaster. Mental health is heavily stigmatized in my culture, so I stayed silent about it. I also didn’t know what was happening to me given my young age.

Tips for Disaster Survivors:

1. DO NOT BE SILENT. My first advice would be to seek help if you have experienced a natural disaster. I was silent about my pain, DON’T BE SILENT ABOUT YOUR PAIN! Communicate your pain to a trusted figure. You may not see the symptoms at first, but they can creep it after your first trigger. Check out https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/coping-after-disaster-trauma for resources on how to gain access to mental health care. The earlier it is addressed, the easier it will be to build habits. Natural disaster trauma is not wildly spoken about at all. Climate change topics, Hurricane season, and disaster events all create extreme anxiety for me, and I have systems in place to help me deal.

2. DO NOT AVOID DOING THE THINGS THAT YOU LOVE. I was a child, but I didn’t feel like it anymore after all that I experienced. It was and still is, difficult for me to cultivate love and engagement with activities that I enjoy. My rationale as a kid was that I didn’t want to get invested in gymnastics, dance, cheer, swimming, or video games again because it all would be taken away again. I developed a strong survival mode that deprived me of simple childhood joys. I didn’t want to gain new friends, new opportunities, or new experiences because I was afraid that I would lose it at any moment. That guarded, panicked mindset I developed became the foundation of how I moved through life. Even now, I am healing those parts of myself as they surface. Little did I know, the healing was in the love. Don’t stop doing what you love because it will help you heal. It will give you an identity outside of your trauma. My trauma became my entire identity while I was trying to protect myself and brace myself for more incoming trauma. Reaching out and getting active in my own time would have allowed me to begin the healing process at an earlier age. Don’t cease your activities, but don’t force yourself when you’re not ready to return. Hold sacred space for yourself on your journey.

3. BE INTENTIONAL WITH HOW YOU CONSUME DISASTER AND CLIMATE INFORMATION. Post-Katrina, I had no one to speak to about my pain until my later high school years. When my anxiety was very bad, I would read articles upon articles about Katrina, consuming triggering content and images that damaged my mental health. I would read ugly comments about the people of New Orleans and I couldn’t understand how people can be so cruel. They didn’t experience the horror that I did. How can they understand? While reading and studying the natural disasters of your area can help you gain a better understanding, and even closure, do so at a healthy pace that doesn’t negatively impact your mental health. I actually wrote my undergraduate senior thesis on Hurricane Katrina and the racist history of Hurricane Betsy. It’s how I finally healed. It was extremely tough, and I had to take extra time to do it because of the mental strain, but I stopped when I couldn’t take any more reading. I stopped when I couldn’t look at another image of flooded New Orleans. I stopped when I couldn’t read anymore about how Black people had no protection of the levee systems we all knew to be in our environment. Be intentional with how you consume content on the disaster that impacts you. Record your triggers and develop a system of care with your mental health care provider.

4. DO NOT SHAME YOURSELF. I lived in shame for 14 years post-Katrina for my experiences. I was a very porous child after Katrina, and people all the way through college made me feel like I was somehow at fault for my experiences. It also didn’t help that people ask insensitive questions, even to this day, about Katrina and New Orleans culture when I mention my home. Shame is one of the heaviest emotions that people who live with PTSD have to deal with. It is a lie. What you went through is valid. You do not need to be in a war zone to experience PTSD. Natural disasters are violent on the body and mind, and what you are going through is so valid. You are valid. Your experiences are valid. Your pain is valid. And so will your healing be.

You are not alone.

To Learn More

The NAACP has a list of environmental justice organizations that I pull a lot of my information from to learn how to support communities still rebuilding after disaster. Where I have done much of my own study comes from the Deep South center for Environmental Justice at Dillard University in New Orleans, LA and the Indigenous Environmental Network in Flagstaff, AZ. With these organizations, we tend to learn of issues that will not make it to the mainstream environmental news as much. Check out this link for environmental justice information: https://www.naacp.org/climate-justice-resources/resource-organizations/.

Nia Burnett is an aspiring marine biologist and planetary scientist who is eager to provide STEM and environmental education access to more people of color. You can find her at @stardustandoceandrops on Instagram and her Venmo is @niamarine19.